The Battle of Salamis & the Triumph of Themistokles

Commentary on Book VIII of Herodotus' Histories

Contents

The Battle of Artemision and Themistokles’ Cunning

As the Battle of Thermopylae was taking place, the Persians and Greeks met at sea in Northern Euboea. This clash became known as the Battle of Artemision. When the Greeks saw the size of the Persian fleet, they considered flight. The native Euboeans tried to persuade the supreme commander, Eurybiades of Sparta, to stay and fight but he was determined to retreat to mainland Greece. The Euboeans then turned to Themistokles and offered him a bribe of thirty talents to make the Greek fleet remain there and fight a sea battle in defense of Euboea. What Themistokles did next was quite cunning:

Themistokles then caused the Hellenes to stay in the following manner: — to Eurybiades he imparted five talents of the sum with the pretence that he was giving it from himself; and when Eurybiades had been persuaded by him to change his resolution, Adeimantos son of Okytos, the Corinthian commander, was the only one of all the others who still made a struggle, saying that he would sail away from Artemision and would not stay with the others. To him therefore Themistokles said with an oath: "Thou at least shalt not leave us, for I will give thee greater gifts than the king of the Medes would send to thee, if thou shouldest desert thy allies."

Thus he spoke, and at the same time he sent to the ship of Adeimantos three talents of silver. So these all had been persuaded by gifts to change their resolution, and at the same time the request of the Euboeans had been gratified and Themistokles himself gained money; and it was not known that he had the rest of the money, but those who received a share of this money were fully persuaded that it had come from the Athenian State for this purpose.

Themistokles was given thirty talents. He used eight to bribe the Spartans and Corinthians, kept twenty-two for himself, and whipped the Persians badly at sea in the ensuing battle. This shows that even in times of existential crisis, honor and virtue are not always the most valuable form of currency. It is important for leaders to be cunning so that they can move things along when honor and virtue are not enough. If Themistokles refused the bribe out of principle to avoid lowering himself, the Euboeans would have been crushed and it is doubtful whether the Greeks would have had the confidence to later challenge the Persians at sea in the decisive Battle of Salamis. Without the confidence gained by this victory, the fleet may have dissolved and the strategic objective of the war would have shifted to a defense of the Peloponnese.

Glory to Kleinias son of Alkibiades

As for the Hellenes those who did best on this day were the Athenians, and of the Athenians Kleinias the son of Alkibiades, who was serving with two hundred man and a ship of his own, furnishing the expense at his own proper cost.

Kleinias is a great contrast to the “elites” in our society today. He combined his high status and wealth with civic virtue. As a result, he gets a shout-out and is memorialized in history for all time. We need to be inspiring our elites to be more like Kleinias. Imagine if the crypto-bros who became millionaires very quickly over the past several years were less fixated on Lambos and Miami broads and more focused on emulating the nobility of Kleinias. Maybe the fate of these crypto-bros is not yet sealed — perhaps they can still put their new-found wealth to great use and become grand organizers and architects of the future. But for now, I do not see this sort of fire in their eyes.

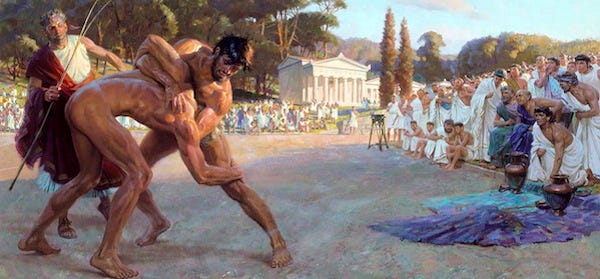

Greek Love of Excellence and Persian Love of Money

As the Persian army continued its march down through Southern Greece, Tigranes son of Artabanos questioned some deserters from Arcadia about what the rest of the Greeks were up to. The Persian commanders were shocked to hear that the Greeks were busy celebrating the Olympic festival:

[The Arcadians said] that the Hellenes were keeping the Olympic festival and were looking on at a contest of athletics and horsemanship. The Persians then inquired again, what was the prize proposed to them, for the sake of which they contended; and they told them of the wreath of olive which is given. Then Tigranes the son of Artabanos uttered a thought which was most noble, though thereby he incurred from the king the reproach of cowardice: for hearing that the prize was a wreath and not money, he could not endure to keep silence, but in the presence of all he spoke these words: "Ah! Mardonios, what kind of men are these against whom thou hast brought us to fight, who make their contest not for money but for honour!"

The Persians had the unfortunate fate of invading Greece at the apex of her glory — where men competed not for money but for excellence alone. Just several generations later, the grandchildren of these great Greeks lost their desire for excellence, willingly accepted Persian money, and descended into abject degeneracy.

Example of Themistokles’ Statesmanship

At this point, Xerxes had reached Athens and set the city ablaze. Fortunately, Themistokles evacuated the population to the island of Salamis, but when news reached them that their city was being destroyed, panic set in and there was a general desire to flee. Themistokles took charge and persuaded the supreme commander, Eurybiades of Sparta, to gather the other generals and convene a war council:

So when they were gathered together, before Eurybiades proposed the discussion of the things for which he had assembled the commanders, Themistokles spoke with much vehemence being very eager to gain his end; and as he was speaking, the Corinthian commander, Adeimantos the son of Okytos, said: "Themistokles, at the games those who stand forth for the contest before the due time are beaten with rods." Themistokles justifying himself said: "Yes, but those who remain behind are not crowned."

This banter is a portrait of the character and statesmanship of Themistokles. Statesmanship requires men to be bold, flexible, and even impulsive at times. You must lean into your instincts and cannot be circumspect. In times of great exigency, principles both large and small may need to be bypassed. Greatness, glory, and victory in great struggles can sometimes require vice or sacrilege. A great statesman will have no bad conscious when facing this reality.

Themistokles Issues a Threat When Logic Does Not Suffice

As deliberations in the war council went on, Themistokles logically laid out the case for why the Greeks must engage the Persians in a decisive naval battle within the straights of Salamis. Defeating the Persian navy would have been the only way to stop the advance of their army down to the Peloponnese. While Themistokles was speaking, Adeimantos of Corinth interjected saying the council should not listen to Themistokles because he was currently a man without a city. Themistokles replied angrily:

"If thou wilt remain here, and remaining here wilt show thyself a good man, well; but if not, thou wilt bring about the overthrow of Hellas, for upon the ships depends all our power in the war. Nay, but do as I advise. If, however, thou shalt not do so, we shall forthwith take up our households and voyage to Siris in Italy, which is ours already of old and the oracles say that it is destined to be colonized by us; and ye, when ye are left alone and deprived of allies such as we are, will remember my words."

While Themistokles was in fact a man without a city and Athens was currently smoldering, they still possessed all the leverage — namely the two-hundred triremes which made up the vast majority of the Greek combined fleet. As a statesman, you need to have a sort of trump card and you must be willing to play it at the right moment when necessary. Thinking politically today, what is our equivalent to Themistokles’ two-hundred triremes? What similar leverage can we employ against our rivals to gain the ultimate advantage? Maybe our two-hundred triremes are not yet built — not yet even imagined.

Themistokles’ Simple Pre-Battle Speech

Before sailing out to give battle to the Persians, Themistokles gave a speech to the marines (just the men that would be fighting on the decks, not necessarily the rowers) and the other commanders.

As the dawn appeared, they made an assembly of those who fought on board the ships and addressed them, Themistokles making a speech which was eloquent beyond the rest; and the substance of it was to set forth all that is better as opposed to that which is worse, of the several things which arise in the nature and constitution of man; and having exhorted them to choose the better, and thus having wound up his speech, he bade them embark in their ships.

Choosing the higher over the lower. This is the essence of nobility in Western civilization.

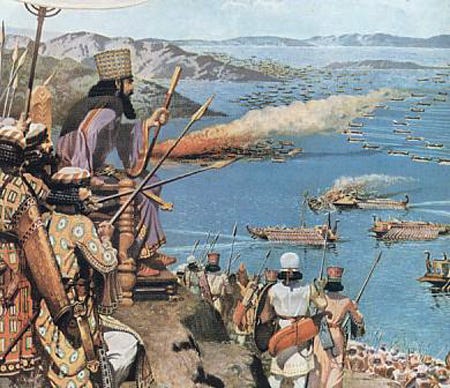

“My men have become women, and my women, men!”

As soon as the battle began, things started to go wrong for the Persians. Xerxes positioned himself on Mount Aigaleos overlooking the straits where he got a front-row seat to watch the history of the world be decided. From his position, Xerxes spotted the ship led by the female general Artemisia. She cleverly evaded some Greek ships pursuing her by ramming a friendly Kalyndian ship and sinking it. This led the pursuing Greeks to think her ship was either friendly or a defector:

Not one of the crew of the Kalyndian ship survived to become her accuser. And Xerxes in answer to that which was said to him is reported to have uttered these words: "My men have become women, and my women men!"

The Bigger They Are, The Harder They Fall

The Battle of Salamis was a massive tactical failure for the Persians. Like Thermopylae on land, the value of their superior numbers was lost when trying to confront skilled opposition in a confined space. It also did not help that none of the Persians seemed to know how to swim:

In this struggle there was slain the commander Ariabignes, son of Darius and brother of Xerxes, and there were slain too many others of note of the Persians and Medes and also of the allies; and of the Hellenes on their part a few; for since they knew how to swim, those whose ships were destroyed and who were not slain in hand-to-hand conflict swam over to Salamis; but of the Barbarians the greater number perished in the sea, not being able to swim.

And when the first ships turned to flight, then it was that the largest number perished, for those who were stationed behind, while endeavoring to pass with their ships to the front in order that they also might display some deed of valour for the king to see, ran into the ships of their own side as they fled.

It is interesting to think that the Battle of Salamis almost never happened. Earlier, we are told that the allies wanted to flee and only the cunning and statesmanship of Themistokles convinced the Greeks to stay and fight. If the other Greeks knew how easy it was going to be to defeat the Persian navy at Salamis, there would have been no debate. Before Salamis, Xerxes’ seemed indomitable — he commanded the largest land and sea invasion force ever assembled. At the sight of this leviathan bearing down upon you, it is understandable why you would want to flee and have little courage to fight. However, the Greeks showed that sometimes all it takes is the courage to resist for fortune to swing greatly in your favor.

Maybe if politicians in our country simply confronted the leviathan bearing down upon us today, that is all it would take to trip it up and have it come crashing down. People think you need these grand plans and elaborate theories, but sometimes all it really takes is a simple display of courage.

Resentment of the Higher Type

Imagine you are Xerxes watching the Battle of Salamis unfold. There is disaster everywhere you look, the hopes of conquering Greece crumbling before your eyes, glory lost forever, and then some annoying peons come to you and start complaining:

It happened also in the course of this confusion that some of the Phoenicians, whose ships had been destroyed, came to the king and accused the Ionians, saying that by means of them their ships had been lost, and that they had been traitors to the cause. Now it so came about that not only the commanders of the Ionians did not lose their lives, but the Phoenicians who accused them received a reward such as I shall tell.

While these men were yet speaking thus, a Samothracian ship charged against an Athenian ship: and as the Athenian ship was being sunk by it, an Aegina ship came up against the Samothracian vessel and ran it down. Then the Samothracian, being skillful javelin-throwers, by hurling cleared off the fighting-men from the ship which had wrecked theirs and then embarked upon it and took possession of it.

This event saved the Ionians from punishment; for when Xerxes saw that they had performed a great exploit, he turned to the Phoenicians (for he was exceedingly vexed and disposed to find fault with all) and bade cut off their heads, in order that they might not, after having been cowards themselves, accuse others who were better men than they.

So even in the despair of defeat, Xerxes has something to teach us: never let lower men gain an advantage over better men. A wise leader will take great precautions against those resentful of the higher type and displays of excellence. Such cowardly men cannot be trusted and will cripple civilization by means of ruining the best men.

Athenians Place a Bounty on Artemisia

Why do you think they did this? Why did Athens take such offense to a woman taking up arms against them? This is forbidden knowledge in our times.

In this sea-fight the Aeginetans were of all the Hellenes the best reported of, and next to them the Athenians; and of the individual men the Aeginetan Polycritos and the Athenians Eumenes of Anagyrus and Ameinias of Pallene, the man who had pursued after Artemisia. Now if he had known that Artemisia was sailing in this ship, he would not have ceased until either he had taken her or had been taken himself; for orders had been given to the Athenian captains, and moreover a prize was offered of ten thousand drachmas for the man who should take her alive; since they thought it intolerable that a woman should make an expedition against Athens. She then, as has been said before, had made her escape; and the others also, whose ships had escaped destruction, were at Phaleron.

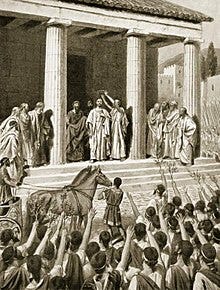

Only the Spartans Gave Themistokles Justice

After the victory at Salamis and the division of the spoils, the Greeks all sailed to the Isthmus of Corinth to present the prize of valor to the man who proved himself most worthy throughout the war. Each commander could cast one vote for first place and one vote for second place. For the first place, they all unanimously chose themselves and for the second place, a majority chose Themistokles.

After the division of the spoil the Hellenes sailed to the Isthmus, to give the prize of valour to him who of all the Hellenes had proved himself the most worthy during this war: and when they had come thither and the commanders distributed their votes at the altar of Poseidon, selecting from the whole number the first and the second in merit, then every one of them gave in his vote for himself, each man thinking that he himself had been the best; but for the second place the greater number of votes came out in agreement, assigning that to Themistokles.

They then were left alone in their votes, while Themistokles in regard to the second place surpassed the rest by far, and although the Hellenes would not give decision of this by reason of envy, but sailed away each to their own city without deciding, yet Themistokles was loudly reported of and was esteemed throughout Hellas to be the man who was the ablest by far of the Hellenes: and since he had not received honour from those who had fought at Salamis, although he was the first in the voting, he went forthwith after this to Lacedaemon, desiring to receive honour there; and the Lacedemonians received him well and gave him great honours.

As a prize of valour they gave to Eurybiades a wreath of olive; and for ability and skill they gave to Themistokles also a wreath of olive, and presented him besides with the chariot which was judged to be the best in Sparta. So having much commended him, they escorted him on his departure with three hundred picked men of the Spartans, the same who are called the "horsemen," as far as the boundaries of Tegea: and he is the only man of all we know to whom the Spartans ever gave escort on his way.

When it comes to praise, what matters foremost is who is giving the praise. It is interesting that Herodotus makes no remarks about the parades and honors Themistokles may have been given at home in Athens, but details at length what honors he was bestowed in Sparta. The Athenians would later go on to ostracize their great hero, while the Spartans alone went out of their way to honor Themistokles. This fact alone convinces me that Themistokles was the greatest Athenian.

When Themistokles arrived back home to Athens, he was immediately attacked by his jealous countrymen:

When however he had come to Athens from Lacedaemon, Timodemos of Aphidnai, one of the opponents of Themistokles, but in other respects not among the men of distinction, maddened by envy attacked him, bringing forward against him his going to Lacedaemon, and saying that it was on account of Athens that he had those marks of honour which he had from the Lacedemonians, and not on his own account.

Then, as Timodemos continued ceaselessly to repeat this, Themistokles said: "I tell thee thus it is — if I had been a native of Belbina I should never have been thus honored by the Spartans; but neither wouldest thou, my friend, even though thou art an Athenian."

Themistokles reminds his fellow citizens of basic hierarchy and rank. How could someone have the audacity to criticize Themistokles? He single-handedly rallied the Greeks and rescued the Athenians from annihilation and slavery. Themistokles was right to smack down this pest, Timodemos. We are reminded of the advice Xerxes gave a few passages earlier: “inferiors must never denigrate their betters.” Never let the low and weak slander higher and better men. Civilization degenerates when the weak and deranged are allowed to tear down the strong and noble. Men like Themistokles must be at the helm and given the highest honor. Nietzsche warns:

There is no harder misfortune in all human destiny than when the powerful of the earth are not also the first human beings. Then everything becomes fake and crooked and monstrous.

The Athenians Vow Never to Medize

As the year 480 BC came to an end, Xerxes crossed back into Asia but left his top commander Mardonios behind with about 300,000 Persians to finish the Greeks. Mardonios sent King Alexandros of Macedonia to Athens with an offer to respect the Athenian autonomy and a promise to rebuild their temples if they will ally with Persia. Mardonios believed that no sensible Greek would think they could stand up to repeated invasions:

To Alexandros the Athenians made answer thus: "Even of ourselves we know so much, that the Mede has a power many times as numerous as ours; so that there is no need for thee to cast this up against us. Nevertheless because we long for liberty we shall defend ourselves as we may be able: and do not thou endeavor to persuade us to make a treaty with the Barbarian, for we on our part shall not be persuaded. And now report to Mardonios that the Athenians say thus — So long as the Sun goes on the same course by which he goes now, we will never make an agreement with Xerxes; but we will go forth to defend ourselves against him, trusting in the gods and the heroes as allies, for whom he had no respect when he set fire to their houses and to their sacred images.

The Athenian response is noble but knowing what happened seventy years later during the Peloponnesian War really sours this entire episode. The Athenians of the Greco-Persian Wars were some of the finest people to have ever existed, but their willingness to later medize with the Persians is telling. How did the Athenians go from this high and noble station to defeat in less than seventy years? Precautions were not made, something decadent was allowed to creep in, and the critical structures were allowed to rot. When circumstances later came to place a heavy weight on the Athenians, the whole edifice would come crashing down. Nietzsche laments the uncanny swiftness of Greek history:

With the Greeks, things go forward swiftly, but also as swiftly downwards; the movement of the whole mechanism is so intensified that a single stone, thrown into its wheels, makes it burst.

One disagreement to a great post.

"Thinking politically today, what is our equivalent to Themistokles’ 200 triremes? What similar leverage can we employ against the Republican Party for example if we wanted to take control of it?"

I don't see the Republican party as the armies (and navy) of Xerxes.

I see the forces of banking/global corporate/socialist govt as the Persians.