Xerxes, a Nietzschean Yes-Sayer

"Do not be afraid! For it is by taking great risks that great power will be won."

It is 484 BC, Darius has died of old age, and his son Xerxes now commands the Persian empire. After quelling a rebellion in Egypt, Xerxes gathered prominent Persians together to discuss a new campaign against Greece. The Athenians had still escaped punishment for their participation in the Ionian Revolt and the sacking of Sardis. Additionally, Xerxes wished to equal his ancestors, Cyrus and Cambyses, who grew the empire by successfully conquering other countries. In my commentary on Herodotus’ Histories Book Three, I suggested that the madness of Cambyses may have been caused in part by his feeling that Persia’s destiny was linked to the conquest of new lands. After his incorporation of Egypt, Cambyses was boxed-in with no easy targets for expansion left. In Xerxes, I see a leader who wants to keep the destiny of his people alive. Sitting idle and managing the empire would be just as detrimental as a failed invasion of Greece.

In this assembly of notable Persians, the only person to voice opposition to the invasion of Greece was a brother of Darius (Xerxes’ uncle) named Artabanos. Artabanos’ reasoning was valid and relied heavily on the reflections of past Persian misadventures. Each time the great Persian kings that Xerxes wished to emulate stretched the bounds of the empire they were met with disaster. Cyrus met his doom in the far East against the Massagetae, Cambyses lost an entire army in the South trying to subdue Ethiopia, and Darius failed twice: once in the North against the Scythians and then again in the West against the Greeks. Artabanos followed this with a warning that the gods humble the mighty and powerful:

"You see how the god strikes with his thunderbolt those creatures that tower above the rest, and does not permit them to be so conspicuous, while those who are small do not at all provoke him. And you see how he always hurls his missiles at those houses and trees that are the largest and tallest. For the god likes to lop off whatever stands out aboe the rest; and so, on a similar principle, a huge army is destroyed by a small one; for whenever the god has become resentful toward an army, he casts panic or lightnening into it, and it is thus completely destroyed through no fault of its own. For the god will not tolerate pride in anyone but himself.”

Xerxes refused Artabanos’ advice and insisted that his honor demanded he punish the Athenians.

“If I fail to punish the Athenians, may I be disowned as the son of Darius son of Hystaspes, the son of Arsames son of Ariaramnes, the son of Teispes son of Cyrus, the son of Cambyses son of Teispes, the son of Achaimenes, since I know well that if we abide in peace, the Athenians will not do the same, but will even lead an army against our country, judging by how they began it all by marching into Asia and setting Sardis on fire.

And so neither side can possibly back down from a conflict now. Whether we actively engage in it or passively suffer what it may bring, we are facing a struggle to determine whether our entire land will come under Greek control or theirs will come under Persian control. For there is no middle ground in our hatred for each other.”

The popular analysis of this episode is to point at Xerxes and accuse him of hubris (just look at how ridiculous they made him look in the 300 movies). In the end, Xerxes ignored the sound advice of Artabanos, marched against the Greeks, was decisively defeated on both land and sea, and had to return home with his tail between his legs. But this popular view of Xerxes is ignorant and shallow. You must understand that Xerxes was in between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, Artabanos’ advice was sound and the historical evidence pointing to failure was clear. On the other hand, Xerxes knew that the destiny of Persia depended upon more expansion and victory over the Greeks. However good Artabanos’ advice was, Xerxes simply could not take it.

I do not see Xerxes as some prideful brick head. Instead, I see him as a Nietzchean child, a genuine yes-sayer:

The child is innocence and forgetting, a new beginning, a game, a wheel rolling out of itself, a first movement, a sacred yes-saying.

Yes, for the game of creation my brothers a sacred yes-saying is required. The spirit wants its will, the one lost to the world now wins its own world.

Logic and the knowledge drawn from experience can dampen the will of great men striving for great ends. Logic and experience are telling Xexes to say “no.” Is it a mark of pride or greatness to say “yes?” Maybe it is just a matter of results: if Xerxes had succeeded maybe he would have been worthy of Cyrus’ or Alexander’s title — the Great.

Is it the mark of hubris for men to ignore logic, discount experience, and strive instead for the greatness of distant shores? What if greatness requires hubris? Is it uncomfortable to imagine that arrogance and pride might be necessary for the attainment of something great and beautiful? Modern man has such a bad conscious towards such questions that he cannot possibly see someone like Xerxes in a positive light.

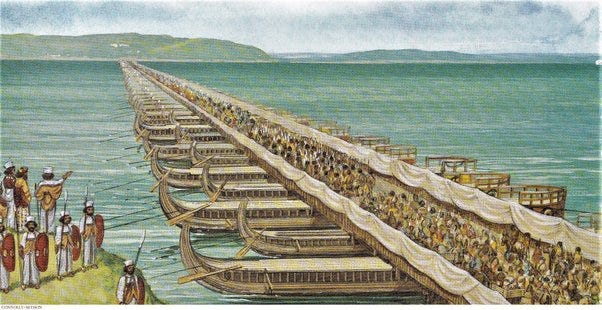

There is one scene in particular that enlightened people will point out in order to slander Xerxes as some sort of clownish megalomaniac. On his march through Asia Minor, a storm swept away a pair of bridges his army was going to use to cross over into Greece.

Xerxes was infuriated when he learned of this; he ordered that the Hellespont was to receive 300 lashes under the whip, and that a pair of iron shackles was to be dropped into the sea. And I have also heard that he sent others to brand the Hellespont.

In any case, he instructed his men to say barbarian and insolent things as they were striking the Hellespont:

"Bitter water, your master is imposing this penalty upon you for wronging him even though you had suffered no injustice from him. And King Xerxes will cross you whether you like it or not. It is for just cause, after all, that no human offers you sacrifice: you are a turbid and briny river!"

Thus he ordered that the sea was to be punished, and also that the supervisors of the bridge over the Hellespont were to be beheaded.

I do not see this as an indictment against Xerxes primarily because he did not recklessly begin this adventure in the first place. The decision to invade Greece was something he wrestled with greatly. Initially, he yielded to Artabanos’ advice even after a voice visited him in his sleep threatening to kill him if he does not invade! The voice visited Xerxes a second time but he did not give into it. Instead, he asked Artabanos to dress in his clothes and sleep in his bed. They reasoned that if the voice visited the disguised Artbanos, it would be evidence of its divine provenance. When the voice eventually visited Artbanos, even he was convinced that the Persians must set out against the Greeks.

What the striking of the Hellespont shows to me is Xerxes’ buy-in. It is a sign of genuine belief in his divine destiny. The burdens of prudence were lifted from his mind, there was no longer a need to hesitate and be circumspect. Now Xerxes could let loose! This is not a sign of his “hubris” but the embodiment of the Nietzchean child, a sacred yes-sayer, someone that has no bad conscious clouding their view of distant shores.

After the Hellespont had been humbled for its insolence, the bridge was repaired and the grand army was prepared to march into Europe. Xerxes positioned his throne on a hill overlooking the army and it is here where Artabanos expresses that he still feared the expedition might fail.

Again, Artabanos’ advice is solid and makes logical sense. He tells Xerxes that there are too few harbors able to shelter his enormous fleet, and leading a million-man army into distant unknown lands would surely devolve into a logistical nightmare. Artabanos’ makes one last appeal declaring that the true superior man is one who listens to his fears and plans around them instead of ignoring these fears altogether.

To this, Xerxes replied:

"Artabanos, you have been fair and reasonable in your judgment of all these concerns, but do not be afraid of everything, and do not, in your considerations, give every factor equal weight. For if you gave every matter that confronts you equal weight, you would never act at all. It is better to confidently confront all eventualities and suffer half of what we dread than to fear every single event before it happens and never to suffer at all.

If you dispute every proposed course but will not point the way to a safe and secure one, then you ought to fail in your argument just as much as the man who argues for the contrary course, since both suggestions for and against thus turn out to be of equal value. How could any human being accurately discern the safe and secure course? I think it can never be done. But for the most part, success tends to come to those who are willing to take action rather than to those who hesitate and consider every detail.

You see how far the power of the Persian Empire has advanced. Well, if the Kings who preceded me had held opinions such as yours, or even if they did not hold them but had followed other advisors such as you, you would never have seen us come as far as we have. As it is, we have reached this point because we have been led by those who were willing to play a dangerous game, for it is by taking great risks that great power will be won.

Xerxes was not afraid, he was comfortable not being able to discern the final fate of his expedition, and he found ultimate consolation in his conviction that fortune favors the bold. While greatness is vindicated by success, the willingness to tempt fate, to be bold, and to reach beyond what others think possible is the prerequisite mark of all great men.

You might reasonably ask, “Well what does great even mean? Should anyone with a crazy idea be encouraged to let loose like this?” Understand, that this is an archetypal conversation, not a moral one. The striving of great men — win or lose, for a cause you may either believe to be “good” or “evil" — is amoral and almost like a violent force of nature. These yes-sayers are the Cyclopes of culture and path-makers of humanity— they unleash frightful energies and earthquakes that cause seismic shifts in our destinies.

This striving of great men can topple old values, destroy a people, and bury their civilizational destiny; and it can awaken new values, a new people, and a new destiny. Xerxes played this dangerous game and lost, but he played his part well nonetheless. Through his great striving and failure, he opened the door for the Greeks to become great and let loose upon the world in turn.

There is also the following shadow to the character. Darius at least risked, somehow, his life in his military campaign against the Scythians (yet fled as a coward). Xerxes never seemed to have gotten close to that point. He simply left after Salamis, and before Platea! The film 300 does a wonderful job at showing these two sides (god like / fearful for his life).

I think I have read this post three times over now, such great work!